Graeme Johnston / 30 December 2022

A perennial topic is whether to conceptualise work, organisations, documents, knowledge – and information generally – in

- a hierarchical way (a ‘tree’)

- a more flexible way – graphs (edges and nodes), tables, misc links / cross-references, labels / tags, flowcharts, mindmaps, Gantt charts, Sankey diagrams – and numerous others

The more flexible approaches have benefits which are so well-known that I won’t try to summarise them here. Trees also have serious limitations and dangers, also well-known.

So. Nobody would claim that trees are suitable for everything. But why are they still popular despite the apparently better fit of other techniques to many domains? Are trees likely to survive? If so, how can their dangers be mitigated?

I think the answer to the popularity and survival questions is that trees, for all their crudeness, are easy to grasp when people have a lot else going on and need to quickly figure out practical questions such as ‘what’s going on?’, ‘who’s in charge here?’, ‘which budget does this come out of?’ or ‘what’s the bigger issue here?’ In reality, the alternative to trees is often not a more sophisticated model. The alternative is often disorder and lack of any insight.

For that reason, I think trees are likely to have a continuing role, assuming that we want to be capable of carrying some widely-shareable schemes in our heads (with all their limitations) rather than just outsourcing knowledge to machines which can process the more sophisticated models more efficiently. And bear in mind how the subtleties of any scheme attenuate the more widely they’re shared between human minds. Perhaps, ironically, good anti-hierarchical things like greater inclusivity, cross-silo working, better reporting and accountability, experts-playing-well-with-others (etc) benefit from simplified models such as trees supplemented by other simplifying devices, such as stories.

The challenge, then, is to avoid mistaking the simplistic tree-map for the more complex territory. There are various techniques that can be used for adding nuance and connection (e.g. labels and links) but at the end of the day I think it’s mainly a matter of

- design – covering an appropriate topic in each tree, and sub-dividing it effectively (and not too much, bearing in mind the opacity of over-complication);

- not taking the trees (and stories) too seriously, and compensating for their imperfections and dangers by adding other information but also by an effort of the mind.

In other words, I think trees will be with us for a while yet. It’s desirable to embrace them, and engage with their limitations rather than abandoning these simple models (and, implicitly, allow the greater sophistication of machines to handle the complexity: how disempowering that would be).

And just to be clear: I’m talking about human thought and communication here, not technology as such.

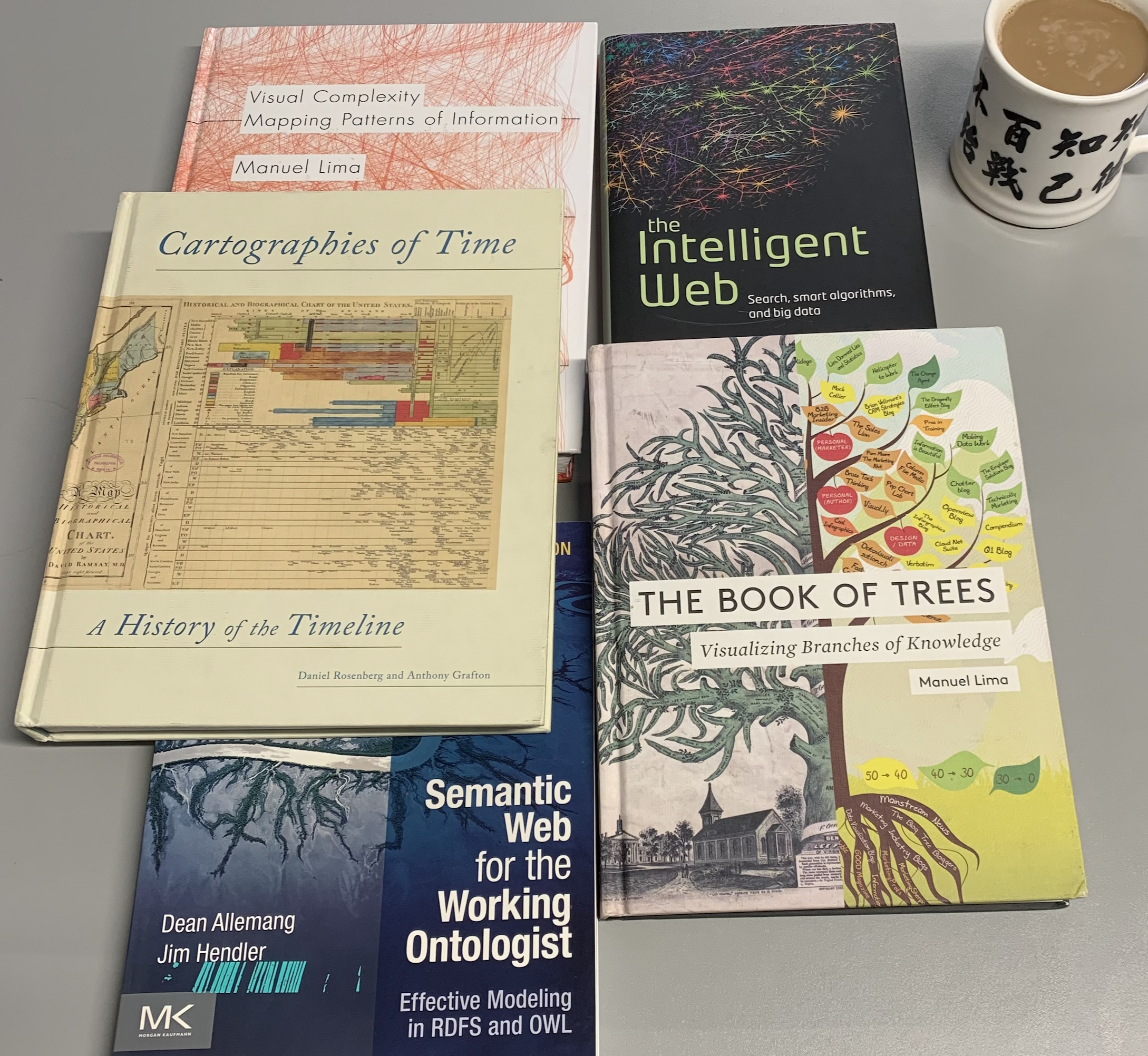

Photo: some books I pulled from the office bookshelf just now. Two (The Book of Trees and Cartographies of Time) contain many rather beautiful, insightful infographics going back decades and, in some cases, centuries. Simplified but highly effective communication tools. The Visual Complexity book has lots of computer-generated infographics, often rather beautiful but less help to me in actually understanding anything. A limitation of my mind, perhaps, but I reckon I may not be the only one. Not a criticism of the editor – as you can see, Manuel Lima is behind both The Book of Trees and Visual Complexity.