Graeme Johnston / 9 January 2023

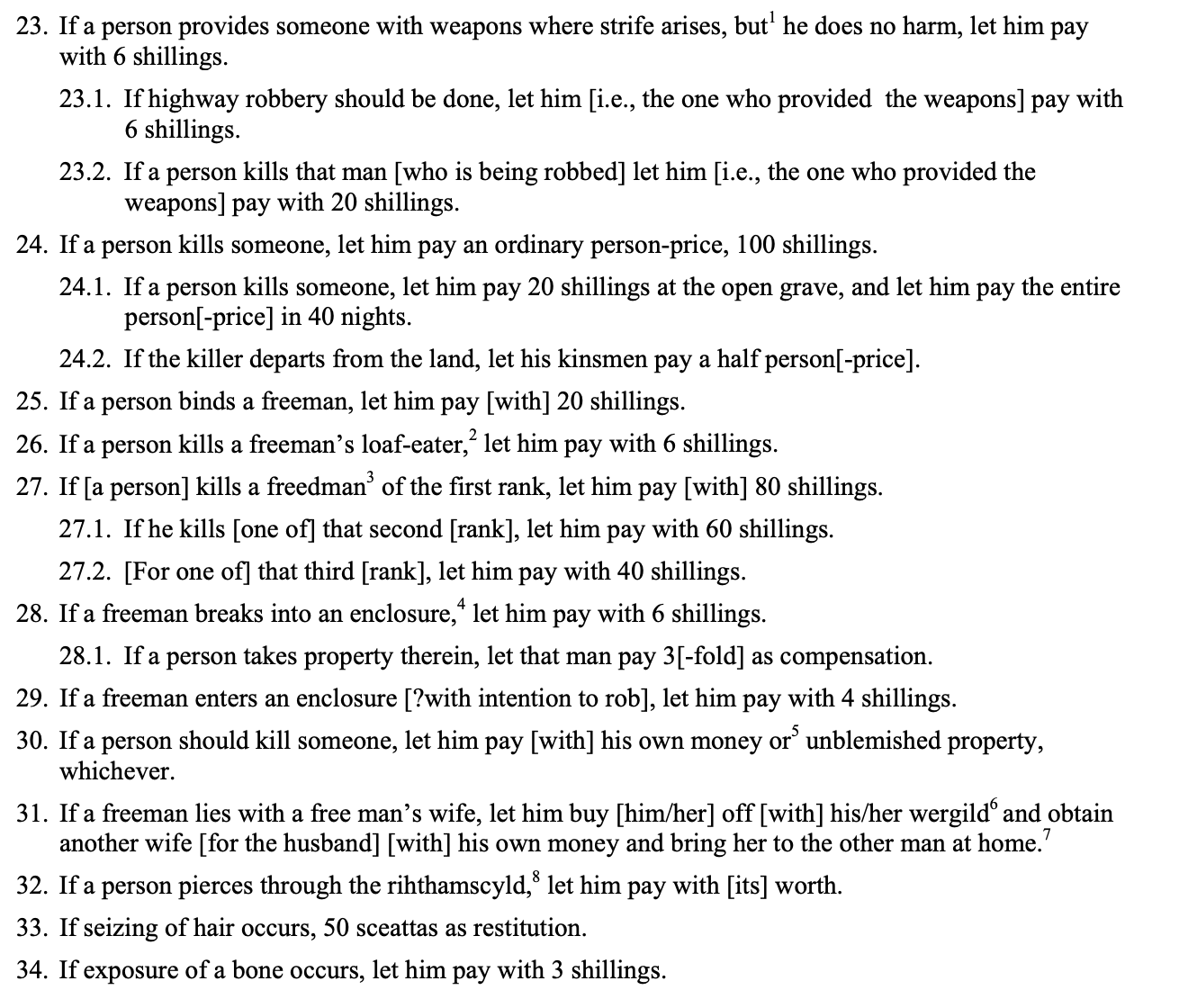

After the Roman period, the first laws surviving in written form for part of what is now England are those of King Æthelberht of Kent, around 1400 years ago. As you can see from the image, they were much concerned with putting a price on unhappy occurrences. A simple system for a time and place in which dispassionate adjudication was not a thing. Imperfect, but better than blood-feuds, assuming that to be the realistic alternative.

Over time, legal systems have developed to tackle a much more complex range of topics and to take consideration of a much wider range of factors. For instance, a defendant’s blameworthiness and a claimant’s actual loss.

But:

New Systems Mean New Problems

When a system is set up to establish some goal, a new entity has come into being – the system itself. No matter what the ‘goal’ of the system, it immediately begins to exhibit systems-behavior, that is, to act according to the general laws that govern the operation of all systems. Now the system itself has to be dealt with. Whereas before there was only the Problem – such as warfare between nations, or garbage collection – there is now an additional universe of problems associated with the functioning or merely the presence of the new system.

John Gall, The Systems Bible (aka Systemantics) (3rd edition, 2002), chapter 1

The resulting problems of access to justice are much discussed (in certain circles) in some countries in which the system has evolved in ways which can work for large businesses – and for individuals with serious wealth – but are oppressive for everyone else.

The amounts of time and money required tend to

- put a serious barrier in the way of most people pursuing their rights against the better-resourced,

- prevent them from defending claims made against them by the better-resourced, and

- risk ruining (or actually ruin) them financially (and in other ways e.g. health) if they choose to pursue or defend – sometimes even if they ‘win.’

State-funded legal aid systems are only ever going to be, at best a part solution to this problem (being yet another system). There is limited funding available for them anyway.

For want of anything better, the concept which therefore appeals to a growing number of people these days is an automated system for resolving issues automatically, or at least presumptively (i.e. subject to human review). To date, that applies mainly to a certain niche of topics readily translatable into numbers – financial trading, some consumer claims, parking tickets. You may well have seen something about this already – if not, google things like rule-based-dispute-resolution, ‘AI and law’, robot lawyers in court, code-as-law and on-chain-dispute-resolution.

Of course, putting a price on injuries to make their compensation more predictable is not entirely new. In addition to Æthelberht’s system (and many others like it), modern legal systems have a ‘tariff’ for certain claims, sometimes laid down transparently, in other contexts unofficial but observable from the data. Examples include English court practice for different types of personal injury or European Court of Human Rights practice for different types of human rights violation.

So, such things existed well before automation. But the increasing interest in, and feasibility of, automation, combined with other factors (such as pressure on public budgets) raises important questions as to the future balance between:

- More automated systems addressing legal issues which are either non-complex (highly rule-bound) or low-consequence-and-readily-reversible.

- More automated systems addressing more complex and higher-consequence issues, but using the kinds of legal concepts similar to those we have known in recent decades and centuries, placing reliance on trusted expert human decision-makers at the end of the day (though with important questions as to the competence of many of those, and on points such as confirmation bias).

- A greater emphasis on efficiency, affordability, simplicity and getting-to-the-point by those working in current human-led legal systems, either ‘in the trenches’ or in positions of authority or influence. Coupled with an increased engagement with topics 1 and 2 in order to sort the good from the bad.

- A largely unsimplified, full-on, familiar type of common law legal process in all its expensive, slow-grinding glory, with limited capability to serve real justice to most people most of the time. And with technology and ‘process improvements’ which tend overall to maintain the nature of that system and even, paradoxically, sustain its increasing complication and cost.

- Increasing amendment of laws to increase their susceptibility to automation. But a combination of a reduction of defences requiring human involvement and an increase in automatic penalties (the price of wrongdoing: can you afford it? maybe…) and automatic enforcement has some potentially serious ‘system’ implications of its own.

Assuming a continuation of our complex societies, economies and problems, there’s no easy or single answer to this. But the issue is not going away, so it’s worth thinking about.

My basic thoughts:

- Points 1 and 2 are happening already. Some of this is acceptable. Some it is even good. But it involves yet more systems. And it also has serious dangers, particularly when addressed without taking competences and safeguards seriously enough.

- We should put more effort into point 3, challenging though it is, given embedded cultures, habits and interests. Culture often eats reform for breakfast, and not in a good way. There are all sorts of contributions possible, whether from individual lawyers or software / data specialists or designers or writers / researchers or people with authority or influence high up in a legal system. And no doubt others.

- The more we fail to address point 3, the more we will likely get of points 4 and 5 (plus a dash of the dangerous end of points 1 and 2), in increasingly unpredictable combinations.

- None of this is binary. The topic is complex and full of trade-offs.

- It would be great to figure out better ways to articulate and measure what is going on here in ways going beyond subjective surveys and case-counts. I have some ideas but want to mull further. Let me know if you’d like to discuss.

In conclusion, another quotation is worth reflecting upon:

“Lord Darlington. What cynics you fellows are!

Cecil Graham. What is a cynic?

Lord Darlington. A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

Cecil Graham. And a sentimentalist, my dear Darlington, is a man who sees an absurd value in everything, and doesn’t know the market price of any single thing.”

Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892)

Source of English translation of extract from the ‘Code’ of Æthelberht